Ok, you may say, animals suffer, but why would someone concerned with suffering focus on animals in a world with so much human suffering to go around? Surely human suffering ought to be addressed before taking up the fight against animal suffering?

Personally, I subscribe to the view that human life and human experience is indeed more valuable and more desirable than a non-human animal experience of life – but not incomparably so, and certainly not indefinitely so. This doesn’t mean there has to be a certain number of animals that are morally equivalent to a human. I believe comparisons can be made even though they be theoretical and uncomfortable, while at the same time I do not desire there to be a moral calculus that would tell us how many B-lives are worth one A-life.

For example, if I was forced to cause a proportionally similar amount of suffering to a chicken or to a pig, say, suffering equivalent to that of a lost limb, I would choose to cause the suffering to the chicken because I assume that action to cause less suffering both in quantity and – perhaps more controversially – in quality. This disagreeable example (and there are much worse thought experiments used by experimental philosophers) may seem intuitively sensible, but in addition to pure intuition we may also attempt to approximate the probability of the volume of suffering experienced by things like the complexity of the animal’s neural and cognitive systems. Yet even this is done not ever knowing the subjective experience of suffering of another being. And, yes, I may well be wrong with this example and future evidence shows that avian suffering is actually more intense and severe than the suffering of large mammals, in which case I ought to adjust my response to this thought experiment accordingly.

Extending comparisons from animal suffering to human suffering seems like a very bad idea. Almost taboo. Surely some things are black and white – animals are animals and humans are humans? The same person who finds that intuition to be common sense may also be a dog owner who loves their canine companion dearly. That person may well value the life of their pet much higher than that of a human stranger on the other side of the world. In doing so, they are actively making cross-species ethical comparisons that they intuitively agree with. But we are experts at living with moral inconsistency. We are forced to be such experts because human intelligence is limited.

Without going into detail of how comparisons should or even could be made, let’s just assume that sentient suffering is somehow comparable, contrastable, even if human suffering should be orders of magnitude more important than the suffering of the next most intelligent exploited animal. Which is the pig, rather uncontroversially. Yes: bacon, ham, pork chops – all made of intelligent, socially complex, family-centered animals who suffer insanely in the process. Hundreds of millions of such sentient beings every year.

The sinews of suffering

Before taking a closer look at animals, consider just a sampling of the dizzying extent of human suffering in the world today.

There are 70 million forcibly displaced people in the world according to the UNHCR due to wars, persecution, and other upheavals. In 2015, 736 million people lived in extreme poverty (under $1.90 per day), and 3.4 billion people still struggle to meet basic needs, living on less than $3.20 per day in lower-middle-income countries or under $5.50 in upper-middle-income countries according to the World Bank. In the US, more than 10 million women and men are subjects of domestic violence every year. The WHO estimates that over 200 million women have been subjected to female genital mutilation. And I could continue this list for hours.

It’s not that I don’t care about human suffering. The degrees and types of cruelty, neglect, inequality, terror, and other sources of human suffering are mind-boggling and too frequently horrifying.

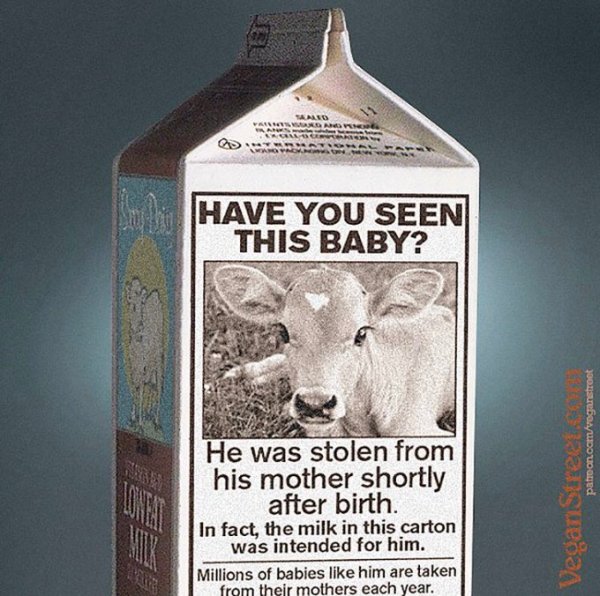

So the question remains, now stronger than ever – why animal rights? My answer is the proportional neglectedness of farmed animals: no matter how you look at things, animal suffering is incredibly neglected.

Let’s take a couple of proxies to quantify neglectedness. In 2017, Americans gave $410 billion dollars to charitable causes. For 2015, Animal Charity Evaluators estimated the top 10 farmed animal outreach organizations to have budgets of $20 million. Let’s assume they count for 50% of the total budgets, and call it $40 million in total to get a conservative overestimate. Note that this would also include governmental grants which are not included in the $410 billion giving figure. Yet to remain conservative, other causes (which are primarily human causes) get approximately 10,250 times the donations that farmed animals do in the US.

There are over 9 billion farmed land animals killed every year in the US (and probably tens of billion of fish). Without exaggeration, 99% of these farmed land animals are born into the factory farming system where suffering is the norm, not the exception, and where cruelty is sanctioned.

Therefore, if we accept that animals can suffer (they can), that we are causing their suffering (we are), and that we should focus our efforts on targets that need the most help (and as I’ve argued, yes, we should), then focusing on animal rights is rational. Even if you wanted to claim that human experience of suffering is 100,000 times more valuable than an animal experience of suffering for purposes of allocating resources, you’d still be left with the equivalent of 90,000 violent human deaths that capped lives of near-constant suffering. As violent and unequal as the US is, there are less than 20,000 violent human deaths per year with billions of dollars in private and public funding aimed at addressing those deaths, as opposed to the $40 million for the suffering of farmed animals.

And very importantly, there are many powerful people and well-funded organizations seeking to eradicate diseases, to alleviate poverty, and to put an end to cruel traditions where humans suffer. Animals have very few such friends, especially in proportion to the problem. While human suffering is very real and horrible, human suffering is not nearly as neglected as animal suffering.

For another angle of how neglected animal suffering is, consider how often you see animal rights discussed in the media. We should be surprised that the constant suffering of billions of our fellow Earth-dwellers in the hands of our fellow humans is not perpetually in the news. But still today the opposite holds: people are surprised and even dismayed that they are asked to question their beliefs and behavior when it comes to their lunch. The rare occasions that animal suffering is discussed in media, it is mostly on topics of outright animal abuse and neglect (usually of dogs, cats, or horses), or the use of animals in entertainment or laboratory testing. As horrible as those cases are, they pale in volume to the suffering on factory farms: in the US, there are 500 animals used and killed on factory farms for every one animal used in a laboratory.

No matter how you dice things, it is especially farmed animals who are neglected and whose suffering challenges us with its moral urgency.

The power in animals

My reasons for focusing on animal rights are both emotional and rational. There is much more to my personal experience and rationale than what I presented here. And I didn’t even get to mention the climate impact of animal agriculture (at least as big as that of all global transport), human health (from carcinogenic meat to health risks of dairy), or existential threats of animal agriculture (a promising breeding ground for antibiotic-resistant pathogens).

But there is one more thing to mention when focusing on animal rights: tractability.

I believe we can make a major positive difference for farmed animals within my lifetime. We may not eliminate animal farming within decades, but it will become undesirable, unprofitable, and widely morally questionable. Within one generation, eating animals and animal products like dairy and eggs will be viewed like smoking is generally viewed in the US today – pretty disgusting but somewhat tolerable. Within two generations, the same practices will be viewed like public executions are viewed today – morally reprehensible, barbaric, still done in some places in the world, but something that ought to be confined into the annals of history.

The issue is tractable because people care. Animals are powerful allies. They are relatable, cute, friendly, and wholesome. They are our link to nature and natural things. They give us support and happiness while our social ties erode and become fewer.

The vast majority of meat eaters care about animals. Many are even a little annoyed by suggestions that they are doing something wrong, because they know they well might be. I know I was.

And back in Finland, on some years there are still sheep at the house I grew up in. If I go, I still meet them and watch them play, graze, and socialize. But I don’t stay for the fall.

Please reach out to me on Twitter with any comments or questions.

Our animal brothers are not menu choices

We the compassionate will be their voices

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love how you manage to convey in such a succinct manner that which takes me an essay. 🙂 Thank you, hon, it’s perfect, as always. ❤

LikeLike

You are so very welcome and thank you ❤️🦜

LikeLike

A touching story, the memories of a child and his friends slaughtered sheep to satisfy “the needs of meat” …

I believe that that sense of powerlessness, in observing the surviving sheep of the carnage, that profound horror that you cannot even erase with your eyes closed, is what unites every human being who sees in the animal a similar one.

The Mikko child will have felt himself dying inside, not having been able to prevent this crime … and I think that this horrible memory is engraved in his flesh with fire, indelible, burning.

But is it necessary to go through such traumatizing experiences to change? Because anthropocentrism and speciesism have reached today’s levels, where, through the fault of the human that kills his fellow human beings, billions of creatures (what we call animals) must also perish.

The choices can be made for different reasons: emotional, rational, ethical, ecological… the basis of every reasoning should be the desire to reach a world of peace, a place where every creature can live as a perfect element of the trophic chain: one of the most important properties of any ecosystem!!!

I’ve been reading a book by J. Lovelock the Revenge of Gaia lately. Although I do not approve of the idea of a solution on nuclear energy, what he describes is imposing in its simplicity and clarity. Everything is connected to another, every system works because it is “balanced”, every creature is necessary… but I think that in the Darwinian theory it would have been better if other creatures had evolved instead of the Pythagoreans.

Now we must continue to fight, we must distort the nefarious habits … unfortunately there will be many battles and there will still be carnage. I will not see it with these eyes, but it will be one of my next reincarnations.

So nice that there are “enlightened” people like Mikko fighting for the voiceless.

Hug and peace :-)claudine

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your words are always so interesting and insightful, beautiful Claudine. Bringing peace and balance is both a noble effort and a necessary cause. Thank you, dear. ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting article Stacey, particularly about his childhood experience. Quite similar to Donald Watson’s, the founder of the UK Vegan Society, who is credited with inventing the word “vegan”. I don’t necessarily view things in the same way as Mikko though. Comparisons between species, and decisions about whose suffering is greatest are not for me. I understand that he is explaining that he focuses on non-human animals rather than humans, because the scale of suffering is so much greater. But I don’t think we can be judges of who suffers most. Suffering, cruelty, exploitation and injustice matter immensely, and need to be challenged, wherever they are found. Thank you for a thought-provoking post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think often, as he mentions briefly, people tend to behave in; make decisions based upon; or view situations in; either a rational or emotional manner (with variations, of course). I think his appeals to a more pragmatic viewpoint, to those more interested in a tangible: a fact, a number, a direction, a plan, etc. Personally, I actually do care as much about the ending of life and global speciesism as I do about the suffering, and I frankly don’t care about any personal benefit I derive from animals to, so to speak, “rationalize” caring about them. (We all benefit in a myriad of ways, of course, whether we’re vegan or not, but I personally don’t factor that into my empathy equation, if that makes sense.)

And I’m visual, so unless I have a picture, I can absolutely miss meaning, and I could be totally wrong about my very basic conclusion referenced in those two points, but I do agree with the premise (implied) that there are those who demand a reason to “choose” one or the other – not that you have to defend your choices – not on this, you don’t – and why can’t you help both? – only that there are those who require it (and quite frankly, those are the people who most likely do nothing at all – for anyone), and, most importantly, that the suffering (and exploitation and death) of animals is massive and basically relentless.

There’s this saying, not sure from whom or where, but it’s something like, “A single death is a tragedy, and a million is a statistic.” This says, yeah, how about billions, and besides it being a stat, it’s WRONG and to ignore it because of OTHER suffering is also wrong: why does the massive suffering of one species automatically negate the massive suffering of another, and not just negate it, but also sanction it? I think rather than accepting a stat as a mere number, he’s using the stat, and the widespread suffering and growth it appropriately reflects, as the basis of an imperative directive.

I do agree with you: I think suffering is suffering, regardless of the sufferer, and should always be challenged. But I also believe that there is suffering with no limits or restrictions, that is sanctioned and applauded, that we can change in many ways with little effort – and that is what we need to do. We also need to make the effort to do so in more difficult ways, regardless of species, because that is what we do, because it’s right, but the unchallenged suffering is often the most accepted.

LikeLike